Michael Harper Speaks with CMarie Fuhrman

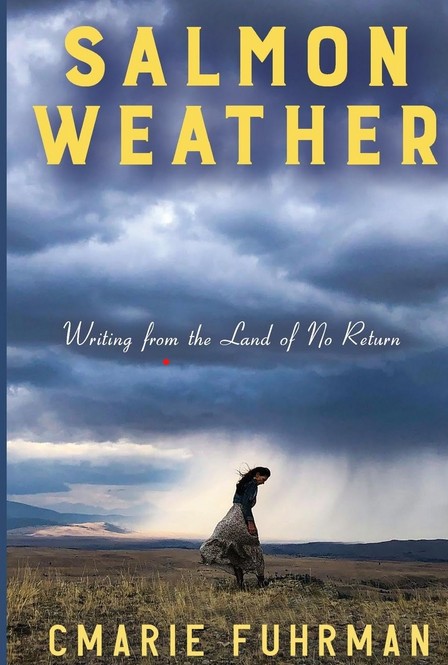

CMarie Fuhrman is an award-winning author, poet, and teacher whose work is deeply rooted in the Western landscape. She is the author of the acclaimed Salmon Weather: Writing from the Land of No Return and the poetry chapbook Camped Beneath the Dam. Fuhrman co-edited two significant and award-winning anthologies: Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, and Poetry and Native Voices: Indigenous Poetry, Craft, and Conversations.

Her voice extends beyond the page, with appearances in documentaries and on stage, bringing her narratives and art to diverse audiences. As the host of Terra Firma, a Colorado Public Radio program, she further explores themes central to her work. Her poetry and nonfiction have been featured or are forthcoming in numerous prestigious publications, including Terrain.org, Emergence Magazine, Alta Magazine, Northwest Review, Yellow Medicine Review, Poetry Northwest, Big Sky Journal, and various anthologies.

CMarie serves as the director of the Elk River Writers Workshop and is an award-winning columnist for The Inlander. She is a fire lookout, the Associate Director for Western Colorado University's low-residency Graduate Program in Creative Writing, where she also teaches nature writing and poetry. A former Idaho Writer in Residence, CMarie Fuhrman resides in the Salmon River Mountains of Idaho, a place that continues to inspire her work and advocacy for beings and land.

MH: Nature tells stories in so many forms that you draw attention to --- tree rings, runoff, rain cycles, just to name a few. How have these forms influenced the shape and form of your own writing?

CM: I absolutely love this question, Michael, and have begun to think about this idea of co-creation-ship more and more. Nature influences my writing. There is a language that Nature uses, from the way wind moves the leaves of the alder to the hundred ways a river speaks, that has changed my own language from line length to lyricalness. Maybe it’s best called the Poetry of Nature. From watching and listening, I have learned how to shape language and tell stories in a way that I feel is most representative of the more-than-human. Longer lines for slow moving rivers. Fragments when speaking of pinecones or cobble. I teach a class where we use the sounds, shapes, and forms to write our own lines, stories, and poems, with an attempt at mimicking rather than describing. It is a wonderful practice.

MH: There are so many instances of you imagining the past, both human and non-human, in this collection. How does imagination work in relation to memory of a place?

CM: It would be easy to rely upon the aphorism, “To know where you are going, you need to know where you have been,” when answering this question, but it would not be complete. At the core, at my core, is a deep love of particular histories. I have always been interested in ghosts. Ghost towns. The idea of hauntedness. Not in the paranormal sense, nor the spooky one, but in words intransitive state. The persistence of spirit. The soul that lingers. And not just the human, but again, more-than-human as well. If I could have a superpower, it would be time travel. I would sit in my little capsule and move back in time and see people, places, and beings as they were. Not to interact or change, but to understand deep time. To feel the immensity of life. And, to some degree, I do this in my writing. As a personal practice it helps me empathize, which is a gift I hope to pass on to the reader. I am for better and worse, sentimental. I am fueled by nostalgia. Both emotions are vital to my creativity and imagination. When I am in place I am aware of those who came before, of their ghosts, and even my own walking along a trail, sitting on a ridgeline. This deep connection to ancestors, human and non, has broadened my understanding, and built a foundation that also imagines a future. Memory then becomes prescience because direct memory, in the conventional sense, is impossible. Imagination then is the bridge, both forward and back, that the reader and I can move across together.

MH: Throughout so much of this collection you are accompanied by biologists and other environmental scientists, most notably your partner Caleb. What perspectives have these relationships brought to your experience of nature and place and, likewise, what does the perspective of the poet/writer add to conversations about nature and conservation?

CM: To know a tree, really know it, takes so many ways of looking. Walking around the base and seeing all sides. Looking up and knowing who lives withing the limbs and beneath the bark and looking too, at the soil and imagining the roots and conversations happening below where we can see. And knowing takes time and the wisdom of others. Caleb’s ways of knowing are poetry of their own. He and other biologists, scientists, and naturalists have helped me to see beyond my own seeing by explaining systems and lifeways that their years of observations and conventional learning have taught them. Most importantly though, I am moved by their passion.

As a poet and writer, I wear my heart on my sleeve for the world to see/read, but these humans, these on the ground researchers and Earth ally’s, they have to tuck all that emotion behind a language that the overculture asks to be stripped of emotion. To relay facts as if they are unconnected to human existence. To remain unbiased. But when I am with them, learning from them, Caleb or Harry Greene, or my friend Jesse Logan who has spent a lifetime with White Bark Pine, I feel their love, their poetry in every sentence they speak. I see it in the way they interact. A hand laid softly upon rough bark in condolence or hope, delight in finding a nest or redd. And tears, oh my god, the tears that these humans shed for our natural world. The ones that cannot go into reports, but instead go into water, to soil, to every effort they make to defend these places and beings they love…that is the language we share and that is the passion that ignites my own. I am not sure I contribute anything to their knowing, but I sure hope I can continue to bear witness, champion, and share their beautiful work of science which is simply a different form of storytelling.

MH: Naming is so complicated in this series of essays. At times, it is a way of simplifying or labeling, and contradictorily it sometimes allows for something infinite to be held in language. This is shown perhaps most starkly in “Lake 8,” where some lakes are labeled “barren” because they have no fish and are not commercially useful. How does this book as a longer form of storytelling act as a way of naming and not naming?

CM: This is a hard one and another challenge for me. Let us hold two things to be true: Naming creates a sense of ownership and naming creates a sense of intimacy and both are potent and many things potent are dangerous. Language is a net that tries to hold these many things and is not always successful. Being a writer offers power and responsibility, in this case choosing to name or not name, which is also dangerous and so I am careful, intentional. And try ridiculously hard to be respectful and understanding of the multiple languages that this land knows, the multiple names of places and beings, and the hierarchical use of naming. That said, I hope that Salmon Weather complicates the way we label and name places. I hope it reveals the variety of names and how language shapes distance, intimacy, and ownership. I hope that readers become more critical and start to examine the language and names used and the way they, themselves, name and use this language. Most important to me is the distance and devaluation that naming can create. To call a deer “game” instead of deer. To call a standing trees “timber” rather than a forest. To label a lake “barren” may be correct in the English use of the word, but since words are merely pointers, the emotional value is lost, and a culture can stop caring. Naming is relationship, which is what I hope readers see, and I hope they wonder about what kind of relationships we can create with words and names.

MH: In this collection, the place has agency and tells its own stories. But it obviously does not speak in a human voice. You as the writer become a type of translator for it. I trusted this process as a reader because you are repeatedly putting your cards on the table, so to speak, or are openly centering your experience by exploring your own contradictions and complicated relationships with the land. How do you view this relationship between yourself, both as storyteller and observer, and a place? What responsibilities do you feel you have in telling these stories?

CM: There is so much value put on a language we speak and hear, but so many other languages exist. Languages our language does not (yet) have words for. What a delight it would be to hear a story from a tree. Or fish. Or Giant Idaho Salamander. Perhaps their way of storying is nothing like ours, probably it is not. Even their sounds and movements may speak in a way that we are not even able to hear. Alas, the constraints of being human. And so, given that constraint, I try to do my best not to speak for but to, maybe as you said, translate, or even reflect. Anyone who has spent a great deal of time with a place or another being understands that there is communication that can only be sensed and perhaps never understood with the minds as we know it.

I believe in the philosophy of the personal being the ecological, which means to me that our inner lives—our grief, healing, identities, relationships—are not separate from but intrinsically embedded in the landscapes we inhabit. For me, it is recognizing that the process we experience internally are sometimes mirrored in Nature and conversely, Nature, along with her health and history shapes who we are.

Honesty matters to me. Vulnerability and truth are compasses I consult. And so it is that I must say that as much as I am aware of the pitfalls of anthropomorphism and anthropocentrism, I am a human relating a story of experiments in understanding life in all it’s myriad forms, including the human form.

So, in stories such as “How I Got Here and Why I’ve Stayed,” the loss of my dad and husband coincided with finding myself, forging a new identity in the vast and complicated landscape of Idaho. It was almost as if the landscape was helping me understand who I am now. In “Lake 8,” place became a mirror for understanding generative and shedding processes by linking fertility to the health of lakes. Even the scars on the landscape from logging roads became analogous to personal wounds. The act of obliterating roads in “A Story of a South Fork Salmon River Logging Road…” becomes a metaphor for a collective healing. A hope for all of humanity. My relationships with the more-than-human are never just about deer or elk or coyote or even dog, it is about confronting my human capacity for love and harm and survival. A reflection on how my history and choices became part of the larger ecological story of the West. In the end, perhaps it is simply recognizing that the land is more than a backdrop for our stories, but a living entity that directly participates in human narratives, and vice versa.

MH: As the Idaho Writer in Residence, you had the opportunity to travel around the state sharing both your work and different types of writing experiences with different communities. What were the biggest surprises you discovered about the people you encountered and their stories of living in a space you share?

CM: What an honor that was. Thank you for remembering. I think the most important lesson I learned was that most Idahoans love Idaho, but that love presents in vastly different ways but is still powerful and real to the one who holds that love. And that hate is not the opposite of love, for hate still shows caring, passion, the opposite is apathy and there are few Idahoans that are apathetic to this state.

MH: As someone who teaches nature writing at Western Colorado University, how do you approach the discourse around nature writing and what perspectives or questions do you ask your students to consider?

CM: I am just back from teaching on the 33, 000-acre Zumwalt Prairie for Fishtrap Outpost, where I also teach nature writing. During the five days we were together, it was my hope to dislodge beliefs taught to us by the overculture. This means becoming acutely aware of the ways our language can reflect or perpetuate the narrow and sometimes harmful perspectives on nature. In all my classes, I want to examine the way words like “wilderness” or “barren” are loaded with judgment and how that judgment can erase deeper histories and the inherent value of life.

Questions I continue to consider with students include:

Whose story is being told, and whose is being silenced? How does our personal identity shape our perception of nature and more=than-human beings? And like you asked earlier, what are our responsibilities as storytellers?

It is important to me to examine contradictions and complicated relations. We discuss the ethical imperative of holding multiple truths and histories. We explore the many ways our backgrounds and the overculture function as lenses and influence how and what we see, value, and choose to write about. Digging into these questions we may not find answers, but I do believe that understanding they exist and understanding the complexities leads to more honest and powerful and convincing writing.

MH: I was in awe of how this collection captures life, renewal, death, grief, joy, and so much more in a way that doesn’t feel like a conventional story arc. All these feelings are humming throughout the writing and existing simultaneously. The last essay beautifully captures this in a quiet moment of reflection that stirs up memories and emotions from all the essays that were read before it. Can you discuss the choices you made in organizing this collection? What pieces came first, and when did the larger story of this collection start falling into place?

CM: I am so glad you noticed this intention!

There are many kinds of traditional storytelling, aren’t there? Depending on our culture. Our backgrounds. Even our families. For me, the fragments make up the whole. Memory is nonlinear but circular and connected.

So maybe it is that my understanding of memory, and of life itself, shaped the way Salmon Weather came together. I didn’t set out to create a linear narrative with rising action, etc. I wanted the collection to be more of a constellation of experiences, emotions, and places wherein themes echo and resonate across essays in the way they do across the actual landscape and the landscape of the mind. The “humming” you felt is what I was hoping for because that is how lived experience feels. We can’t escape one emotion for another, just like many ecological systems they coexist and inform and depend on each other.

The larger story, the cohesive narrative, began to show in revision. I realized that the individual pieces, though written over a decade in response to different stimuli or sparks, were all orbiting around certain central themes. From my evolving identity as an adopted and mixed-blood Native woman, the relationships between human and more-than-human lives, the history of the West, and the beautifully consistent cycle of loss and renewal were the threads that held the stories together, like pieces of a quilt. The very conscious decision which I write about in “How I Got Here and Why I Stayed,” to leave the stories as they were originally written, despite new knowledge, was critical. This allowed the collection to truly reflect a journey, an evolution of understanding, rather than some fixed retrospective. The chronological order of my experiences in my life isn’t perfectly linear in the book because my emotions and insights don’t arise in that way. A moment of hope in one essay might be followed by deep grief in another, just like life.

There is also some intuition that comes in. I got a feel for where things belonged. And so it was with the final essay, “This Bend in the River or What May Have Been a Dream.” It felt right to place this story at the end to bring a sense of culmination not through a tidy resolution, but through enduring presence and hope. The story ties together strands of memory, individual, cultural, and historical, with the narrative of a river and land. I hope this leaves the reader with a sense of continuous possibility, even now, amidst a time of profound and acknowledged loss. I wanted to offer an invitation to see the whole collection as a living cycle, much like the river herself.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

© 2025 Iron Oak Editions

Stay Connected to Our Literary Community. Subscribe to Our Newsletter

August 18, 2025

Michael Harper teaches at Northern New Mexico College. His most recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Ninth Letter, X-R-A-Y, Hobart, Fugue, Terrain.org, The Los Angeles Review, and others.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________